The morning after my car accident, I found out that my iPhone had survived. I was elated. It truly felt as good as finding out that I had kept my arm.

The elation did not immediately dissipate. My first day in the ICU, all of my friends rolled through. It was a party. A guitar was even taken out at one point. And having been 8 years sober, I now had a button in my hospital bed that dispensed morphine whenever I clicked it: Click click click click click click click. Click. Click. Clickclickclick.

My friend Harper, who was in the car and had helped save me from the crash, was one of the first people that visited me.

I told her, “I’m so grateful nothing happened to my brain. I could have lost my ability to communicate…”

Harper looked at me and said, “I’m sorry but I have no idea what you’re saying right now.”

Like I said, we had fun. The car accident felt like an anecdote. Something funny and random (!) that had happened. It did not yet feel like a life altering event.

Until reality, as it so often does, made itself known.

The doctors came into my party room, uninvited, and told me that I had lost important muscles in my left arm. They believed I’d never be able to use it again. I began to sob, in front of my party of friends. I didn’t even have the energy to be embarrassed about it.

I learned that I had lost most of the head of my humerous bone, the round top of your shoulder. You can see this now, if you look at me closely. I’m a little asymmetrical and my left shoulder cuts straight down, like a cliff. This would bother me more, but as is true for most women, there are so many parts of my body that bother me… my cliff shoulder doesn’t even make the top 5.

In between laughing with my friends, sobbing uncontrollably over my new disability, and getting high on morphine, I, ever the workaholic, also began to tackle some emails and texts. I concentrated through the fog of my click-click morphine drip, and responded to every single person who had sent the text, “U ok?” even if they were just acquaintances. Depending on how high I was, my texts ranged from “Not really! Haha, kind of banged up” to “I’m in the hospital because I won’t stop farting” or “I heard Lorne Michaels was in the car that hit me.” Someone texted me to ask if my boss was safe, forgetting that I was also in the car, so I responded “He’s fine but I’ll never use my left arm again.” Just to try and transmute some of my pain onto him.

As my stay in the hospital lengthened, and I began having more surgeries, I was introduced to a pain the likes I’d never experienced before, nor since. You would think that my morphine would cover it all. But I have learned that there is a pain so vicious that you will literally vomit all over your tits, while crying for your mother. I remember being covered in vomit, crying “Somebody has to help me.” I couldn’t accept a reality where people could be in this much pain with no relief.

My friends stopped coming to the ICU as my body couldn’t even take the stimulation of visitors, and after all, the novelty was gone. It was no longer one exciting night in the hospital. It was becoming… a lifestyle. Now alone with only my family as visitors, I regressed back into being a child. I cried easily. I despaired over my future. A new fear was born, one that would stay with me for the next six years: “Who will love me like this?”

But there were always moments of hope. Hope that if I managed everything correctly, perfectly, I’d end up fine. No scars. Good as new. Fixed. All I had to do was delicately contort my reality, so slowly, it wouldn’t even notice. I would manage my surroundings. I would arrange, research and plan for a better outcome. So, after my friends and family determined my current hospital didn’t have experienced enough reconstructive surgeons, I got myself transferred to Cedars Sinai. My boss pulled some strings to get me an amazing medical team at Cedars, and I was optimistic about my care there.

But the night I landed at Cedars, a doctor threatened to take my fingers. I guess labeling it as a “threat” is unfair, but that’s just what it feels like when someone says they might need to take your fingers. He told me he wasn’t sure they would heal, and he would keep his eyes on them. This… was a random stranger, threatening to deform me. Is this what the best doctors had for me? Was it still the middle ages when it came to medicine? Was I safe anywhere?

My grandfather once told me a story from his childhood: He had closed a classroom window on his middle finger, and it fell into the bushes outside of his school. Guess what they did? They sewed that little fucker back on. So why were all these surgeons acting as though I was Mount Everest?

I was going to meet with my new shoulder surgeon the next morning. I was prepared to hear how long it would take me to heal from this accident. I had already planned his answer for him. This is something I do a lot: I kindly but firmly offer reality my plans. So, I would ask him how long my recovery would be, and he would tell me nine months. Maybe it would be longer, maybe he’d say a year. But no, he was going to say nine months. And he would be confident in his ability to fix me. I knew it was going to go that way. I was going to will it to go that way.

My shoulder surgeon came to meet me in my hospital room. He was wearing a suit, and I was naked under a flimsy gown, but our introduction felt formal, professional. I was excited, as he had been described as a miracle worker. But his eyes were filled with pity, and he spoke softly, preparing me for the bad news. I tried joking, hoping to change his attitude, bring the room back up. Finally, I asked him how long it would take for me to recover from this. He told me it would take years, years for me to recover from what had happened.

I left my body. I can see myself now, how hard I cried then. This was happening to someone different. There is a line in an Elliott Smith song where he just sings, “This is not my life.” And that’s what I kept thinking: Wrong life. You’ve got the wrong person. This isn’t happening to me, because that would mean my life is a tragedy, and I had been living with the firm belief it would be a romantic comedy.

But, as I would learn over and over again in the hospital: Reality keeps chugging. Time doesn’t stop for your sorrow. The days keep churning out sunrises despite your pain. The cruelest part? People have lives, that continue, lives that do not even pause to rubberneck at your catastrophic event.

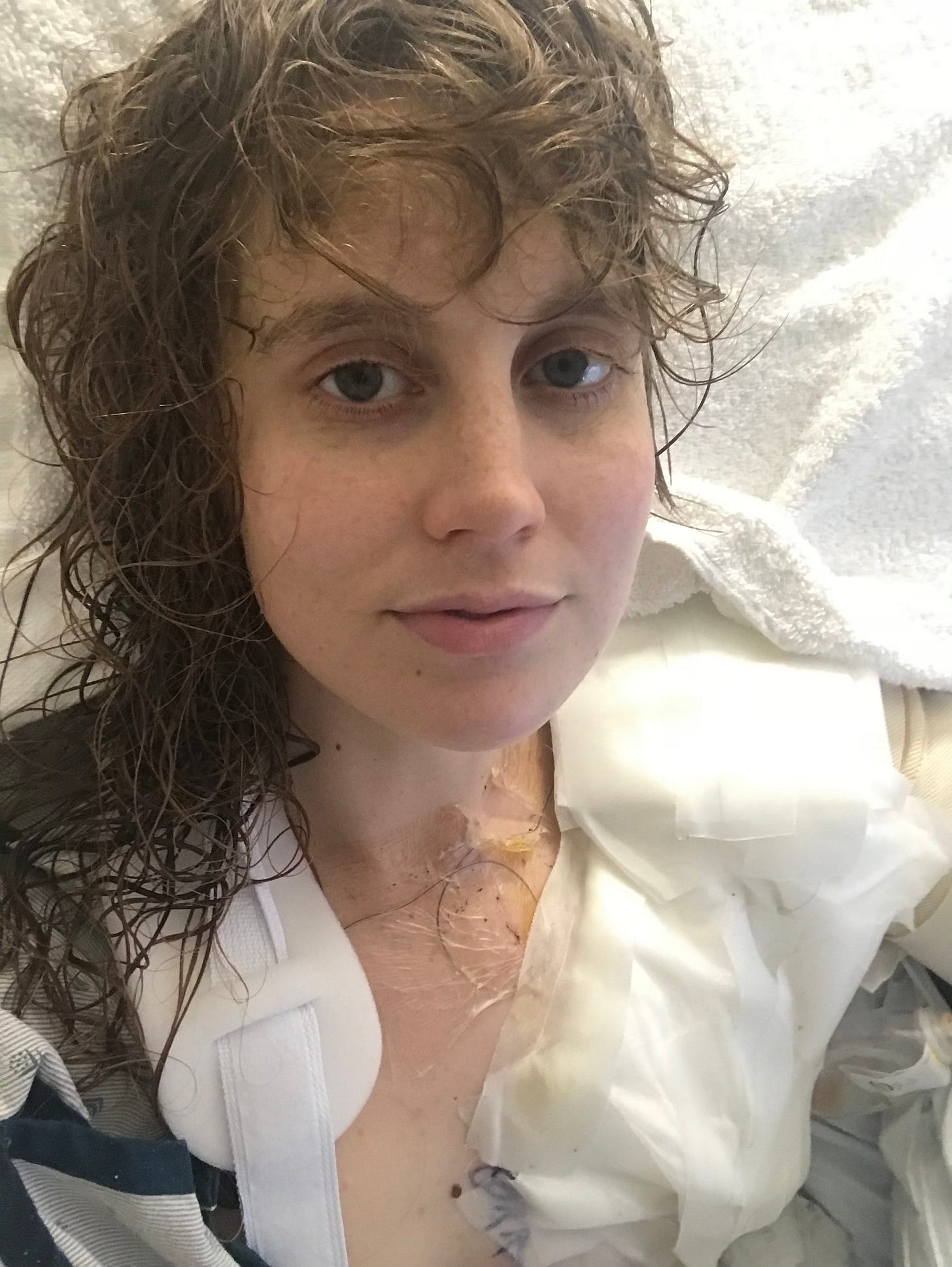

So, on my 28th birthday, I went through an eight-hour surgery. They applied skin grafts to my left arm, and breast. They cut a piece of my forearm and rotated it to cover my left hand. They cut a piece of skin and muscle from my back and flipped it to cover the defect in my left shoulder. I can’t emphasize enough how little knowledge I had about any of these procedures.

When I came to, I was in excruciating pain, and I needed blood transfusions to stay alert. My lips were chapped and I asked for help. My mother was arguing with the nurses, telling them that the pain meds weren’t adequate. I began to receive Oxycotin. Ever heard of her?

The recovery from this surgery was a beast. I stopped being able to sleep through the night. My co-workers had dropped off an enormous collection of party balloons for my birthday, and in the middle of the night I would stare at them, high off opiates, watching them morph into monsters. I began to laugh from the pain. It was ridiculous. It had cornered me. What else was I supposed to do?

Thankfully, the doctors finally decided my pain was unsustainable. They wanted to do a nerve block, literally blocking my nerves from my arm, so I could stop feeling the pain. This procedure, so complex that only two men at Cedars knew how to do it, ended up working. I stopped being able to feel my arm. I didn’t feel pain. I felt close to nothing.

I began to relax. I gave up any control over my situation, over reality. I surrendered as much as I could. Now, I just had to recover, and go into surgeries. I began to look forward the anesthesia, the ego death, the countdown to obliteration.

I don’t know what to tell you, I love drugs! I love disappearing. I love nothing over something. I’ll always take absence over presence. In my twenties I used to fear death, my ego so large that the idea of it disappearing someday was unthinkable: I would get old and die?! What the hell? How depressing was that? Now, at the age of 34, I look forward to death. Not in some dark, suicidal way. More like how old men look forward to a steam room. I’ll get to sit down, forever. And as someone who has gotten close to death, I just want to take a moment to be woo-woo. I intuitively felt something that night: There is nothing to fear there.

But, still alive, I was encouraged to aid in my own recovery. So, I began walking around the hospital, looking at all the mediocre art on the walls. I also began to get to know the nurses.

I was fascinated by the nurses as they dispensed care liberally, wearing their hearts on their sleeves, almost absurdly angelic. Nurses would give me sponge baths casually, using a sponge to literally scrub me everywhere. One nurse told me she treated all of her patients as if they were her mother, or daughter, or grandmother. One nurse sang to me, while she took care of my incision sites. One nurse couldn’t help but cry every time I cried. So, we often cried together. Then, she’d show me pictures of her posing with her cop boyfriend’s gun, and I’d show her pictures of my boyfriend, smiling with a joint in his mouth. In another reality, we were just friends: one sick and one well.

If we were friends, I would have to contend with the fact that she had a cop boyfriend, but you’re missing the point. We cried together.

With all of this incredible care… I began to understand that there may be some medical expenses. It turns out, there is a health insurance crisis in this country, where if you get sick, you also get poor. What a great system! During the worst moments of your life, they make sure you really lose everything.

The night I had arrived at the hospital, they asked me for my insurance. Let me remind you: Doctors had just told me I would lose my fingers, maybe my hand, maybe my arm. And they had the audacity to ask for money in exchange. So, my hands, wet with blood, slipped around on my iPhone screen as I pulled up my insurance cards for my nurse. It’s literally as if I had got stabbed in an alley, and before patching me up, someone had asked for three hundred dollars.

Except… instead of three hundred dollars. I would soon learn that my medical bills, after three weeks in the hospital, were for almost three million dollars. You read that correctly. Three million dollars. Now, I don’t know who is reading this, and I can’t pretend to know anything about your financial situation, but three million dollars is a lot of money to me and to everyone I know. And I had… less than that. I had almost three million dollars less than what my insurance was being billed for.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Carolina Barlow's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.